As global concerns were high over inflation running hot, several Latin American policymakers managed to keep a cool head. Without hesitation, they increased interest rates rapidly and aggressively as inflation started to raise its ugly head. The Brazilian central bank already started its series of rate hikes in March 2021 as one of the first countries in the world. This monetary policy was significantly ahead of the curve compared to its Northern counterpart in the U.S., where the Federal Reserve started its rate hike cycle a year later in March 2022. Against all odds, many of its economies have managed to sail through rough waters relatively well due to the economic-orthodox stance of their policymakers. Argentina and Venezuela are the exceptions to the rule as they continue to struggle with implementing sound monetary and fiscal policies.

LatAm central banks raised interest rates despite pandemic issues

The Latin American region was the hardest-hit region during the COVID pandemic. Its mortality rates were disproportionately higher compared to other parts of the world. Latin America has a population of 670 million inhabitants, which is only 8,42% of the worldwide population. Still, it suffered 1.74 million deaths measured from the beginning of the pandemic to early December 2022. That makes for 26% of the worldwide mortality rate coming from Latin America. The gravity of the crisis is attributed to strained and underfunded health systems, slow vaccination rates, deep social inequalities, and increased poverty.

The demographics in Latin America – with high levels of income inequality and a majority of the population living in poverty – make it a breeding ground for social turmoil when household spending budgets get squeezed by inflation. The poor are the first and the hardest to be hit by the effects of inflation. Therefore, they are prone to head to the streets to show their discontent over increasing prices of necessities such as food and gasoline. Hyperinflation has marked the region’s history several times in the past. Central bankers learned from previous experiences and quickly turned hawkish to combat inflation despite the challenges faced by the COVID pandemic.

Interdependence with the U.S. remains high

The CLAAF (Comité Latino Americano de Asuntos Financieros – Latin American Committee on Macroeconomic and Financial Issues) identified the root of the inflation spike in cost price pressures in global supply chains due to lockdowns and the unprecedented increase of aggregated demand due to excessive monetary expansion in the U.S. and other advanced economies. As identified by the committee, inflation managed to find its way to Latin America through:

- Import of inflation due to the dominant role of the U.S. Dollar in global, but especially Latin American region’s transactions

- Expectations of sharp monetary tightening in the U.S. would lead to capital outflows from Latin America and subsequent depreciation of local currencies

- Fiscal expansions in several LatAm countries to combat the economic effects of COVID were not quickly enough reversed even though consumption had recovered (Argentina, Venezuela)

The expectation is that interest rates in Latin America will remain elevated as inflation risks have not subsided yet. Early-rate hikers have stalled any further increases in the policy rates to wait and see what next steps the Federal Reserve will take. Inflation has yet to be contained in the U.S. and might require a continuation of tight monetary policy. Monetary policy in Latin America remains heavily dependent on developments in the U.S. as the Federal Reserve will take the first steps to return to a lower policy rate environment.

Economic orthodoxy enabled Latin America to weather the storm

Central banks and ministries of finance have cleaned ship by contracting better-qualified staff with economists who have studied in some of the top universities in the world. More effective regulation and increased professionalism have improved the professionalism of its institutions. Since the 1990s, central banks have operated independently on the long-term goal of price stability. Clear objectives on price stability improved the legitimacy of Latin American institutions on a global stage as investors gained confidence in the predictability of monetary policies. Furthermore, regional authorities have armored themselves against shocks with more solid foreign reserves and a debt mainly denominated in the local currency.

Real interest rates achieved in most of LatAm whereas developed markets still struggle

The rapid response of central banks in Latin America to raise the interest rates aggressively to double digits has resulted in positive real interest rates in the region’s early rate hikers Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Colombia and Peru have not yet achieved to get their real interest rates in positive territory although they are just in the negative. Colombia started its rate hike cycle later and still experiences elevated levels of inflation. Ongoing social upheaval with protests in Peru causes elevated price levels due to supply chain disruptions increasing costs. In developed markets, only the U.S. has managed to achieve a neutral interest rate of 0% as Japan and Europe still have severely negative real interest rates.

| Nominal interest rate | CPI inflation rate | Real interest rate | |

| Brazil | 13,75% | 4,65% | 9,10% |

| Chile | 11,25% | 11,10% | 0,15% |

| Colombia | 13,00% | 13,34% | -0,34% |

| Peru | 7,75% | 8,40% | -0,65% |

| Mexico | 11,00% | 6,86% | 4,14% |

| U.S. | 5,00% | 5,00% | 0,00% |

| Europe | 3,50% | 6,90% | -3,40% |

| Japan | -0,10% | 3,30% | -3,40% |

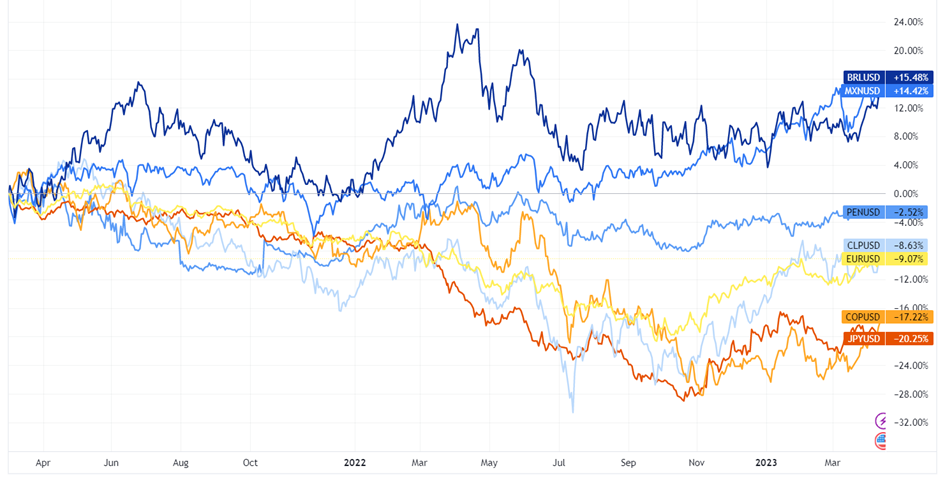

LatAm FX currencies have faired relatively well

The saying goes that as the U.S. sneezes, Latin America catches a cold. Traditionally, the region sees strong depreciation of its currencies when the U.S. experiences economic turmoil. Rising interest rates in the U.S. generally lead to capital outflows from Latin America and subsequent currency depreciations. Sound monetary and fiscal policies of policymakers in Latin America have prevented severe currency collapses to the U.S. Dollar. Taking the starting point with the first policy rate hikes in March 2021 by the Brazilian Central Bank shows that early adopters Brazil and Mexico gained strength against the U.S. Dollar. The Peruvian Sol and Chilean Peso lost some of their strength to the U.S. Dollar but performed better than the Euro. The worst performer amongst Latin American currencies was the Colombian Peso plagued by sustained food inflation but still performing better than the Japanese Yen. The Chilean and Colombian Peso are also weak performers as they suffer from a general distrust of investors in the left-wing politicians who came to power.

Stability of strong institutions challenged by the Second Pink Tide movement

So far so good, but not out of the macroeconomic woods. Inflation seems to have been contained in the region and policymakers maneuvered the economies fairly well through interest rate hikes in the U.S., but that does not have to mean that the Federal Reserve’s battle with inflation is done yet. Latin American policymakers will keep a close eye on further steps made by the Federal Reserve.

Furthermore, the region is experiencing a second wind of left-wing politicians referred to as the Second Pink Tide challenging the independence of central banks. It is hard to alleviate poverty and diffuse social tensions with too meager economic growth forecasted at 2% for 2023 (IMF). Some left-wing politicians call for lower interest rates to increase public spending to alleviate post-pandemic poverty. Brazil recently returned to the target range currently at 1,75% to 4,75% for the first time since 2021. With a 9,10% real interest rate, the pressure to drop the policy rate is increasing. The future will tell whether Latin America’s institutions will be robust enough to maintain their independence under political pressure.